experience design in health care

Challenge: Increase the number of patients being referred to transplant and broaden their perceived kidney options.

My Role: As a Business Designer I built out a chance package, filled with industry best practices, and guided implementation within dialysis centers. I also led user interviews and built out metrics and data visualization for our digital solutions.

Team Structure: Service Design Lead, Business Designer (me), Visual Designer, Project Manager

Summary: A key player in Healthcare asked Fjord DC to craft two products that would: 1. increase the number of patients referred from dialysis centers to transplant centers and 2. increase the motivation for patients to choose a High-KDPI (Kidney Donor Profile Index) kidney. Through a series of user interviews we recorded patient stories regarding their journey with kidney failure and thoughtfully crafted them into a portable motivational booklet. In this book, we included inspirational quotes and helpful advice to inspire future patients to take charge of their own health journey. We balanced this focus on patients with an additional product focused on dialysis center efforts: a Change Package recommending 68 best practice initiatives, varying in levels of effort and impact, and backed by scientific research with supported success across industries.

THE PROBLEM

A diagnosis of kidney failure, or End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), means that a patient's kidneys can no longer filter blood — an essential life function. In order to survive, people with ESRD have two choices: to receive ongoing dialysis treatment or get a kidney transplant. The average wait time to get a transplant is 3-5 years, though in some states in can be more than 10 years. There are about 100,000 people on a kidney transplant center wait list. Most patients live on dialysis while they wait for their new kidney.

Dialysis is life consuming. Most patients with kidney failure spend four hours every other day receiving treatment at a dialysis center. Not only does dialysis impact patients' quality of life, the United States government spends nearly $28 billion dollars each year on dialysis treatment. Medical research consistently shows that patients who receive a kidney transplant have better long-term health outcomes and improved quality of life over those on dialysis.

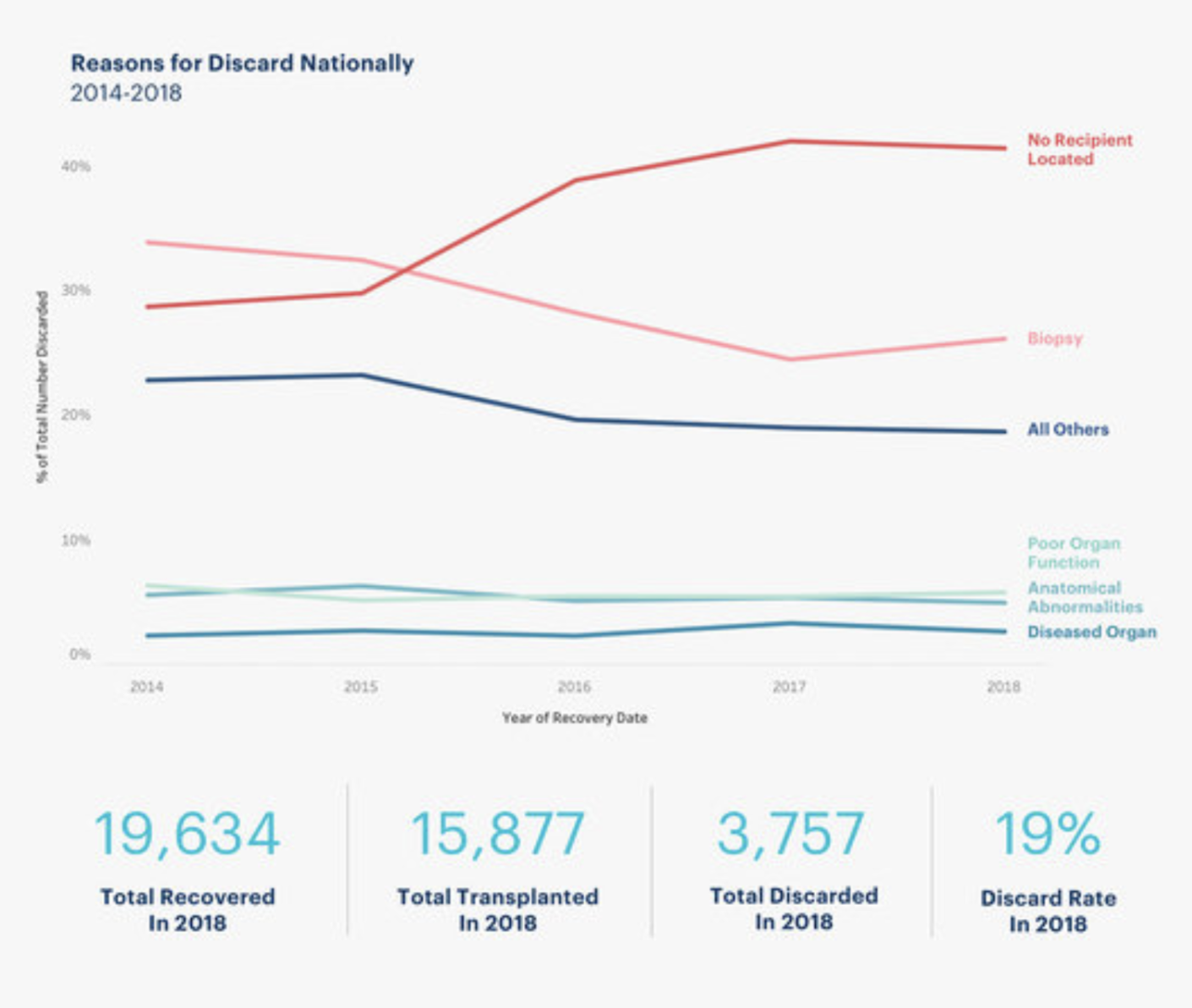

Twenty thousand kidneys are donated from deceased donors each year but twenty thousand new patients are diagnosed with ESRD each year. And with a hundred thousand patients already waiting for a kidney, the demand continuously outpaces the supply. Because of this, eleven people die every day waiting for a kidney transplant in the United States. To make matters worse, of all donated kidneys, about 19% are discarded instead of transplanted into patients.

THE process

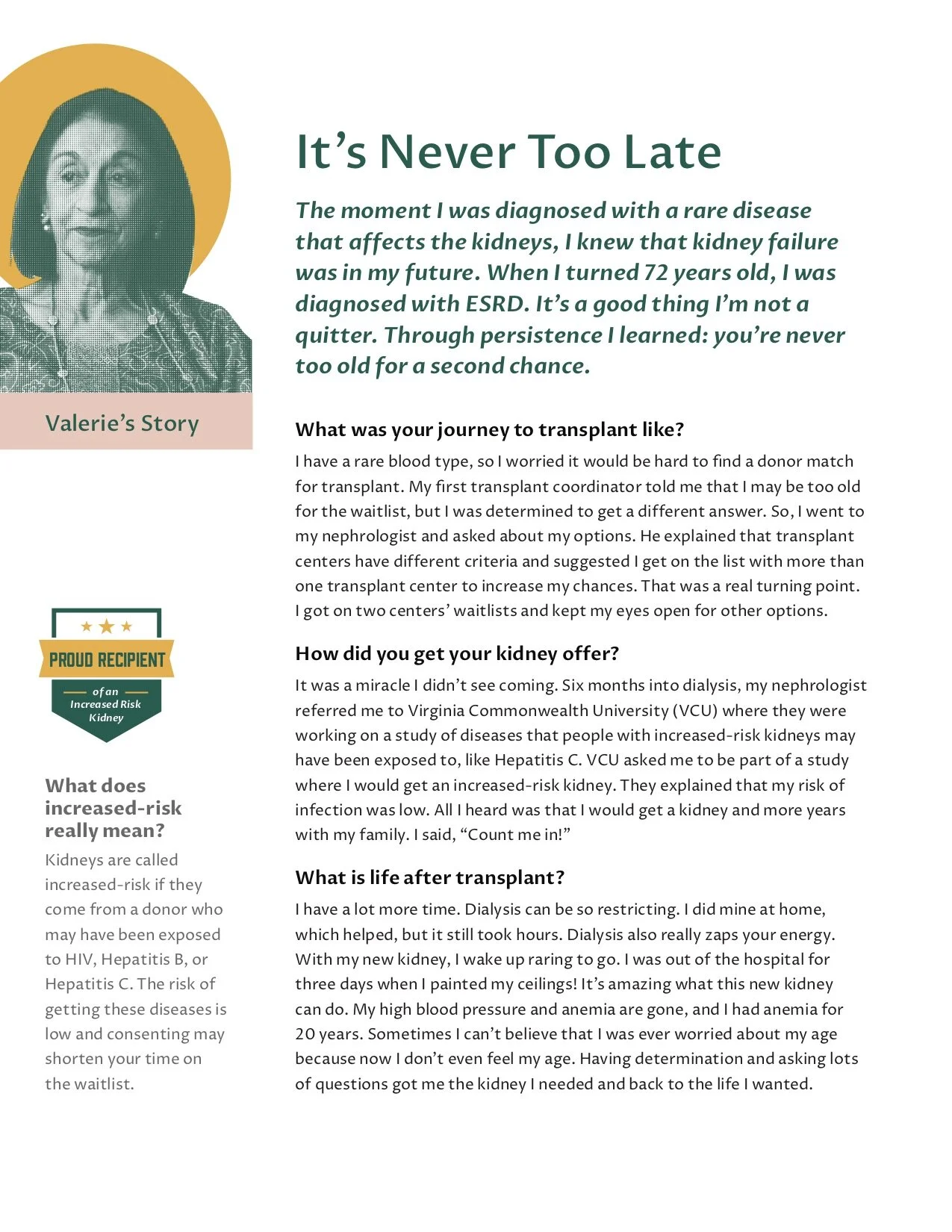

We recorded patient stories through a series of ethnographic interviews and thoughtfully crafted them into user stories: establishing a narrative, defining key terms and experiences, maintaining the user’s voice, and embedding motivation throughout. The portable booklet contains 5 user stories complete with inspirational quotes, easy to follow journey segments, and take-away advice. The booklet can be placed in dialysis centers for patients to read while in treatment in hopes of providing accurate information and inspiration to consider transplant. Our goal was to reframe transplant as the natural step after dialysis in the ESRD journey and encourage patients’ to consider broader kidney options. We simplified the terms and process of kidney transplants so users can better understand the benefits of transplant. We included “life after transplant” segments in the user stories as a way to further showcase the benefits of transplant and to help users visualize their potential future as a foundation for motivation. Finally, we rebranded High Risk/High-KDPI kidneys as something to celebrate.

We were also keenly aware of the impact dialysis centers have on patient journeys and the critical role they could play in increasing patient referral rates and encouraging a pro High-KDPI culture. We created a Change Package for the dialysis centers, consisting of 68 potential best practice initiatives, each with critical steps for success and example templates for reference. The initiatives were grouped by main idea or driver that would move the needle on a key theme (information and access, patient motivation, dialysis center processes, and support systems). We prioritized critical concepts and assessed initiative owner and level of effort to help users identify feasibility within their centers. While many of our initiatives were found best practices within healthcare we also included successful interventions practiced and applied in other industries, such as the psychology of motivation, design thinking, and learning science, which could be translated into healthcare to enable further innovation.

changing the bias behavior Upstream increased the number of viable kidneys available for patients to accept

Behavioral Change solutions

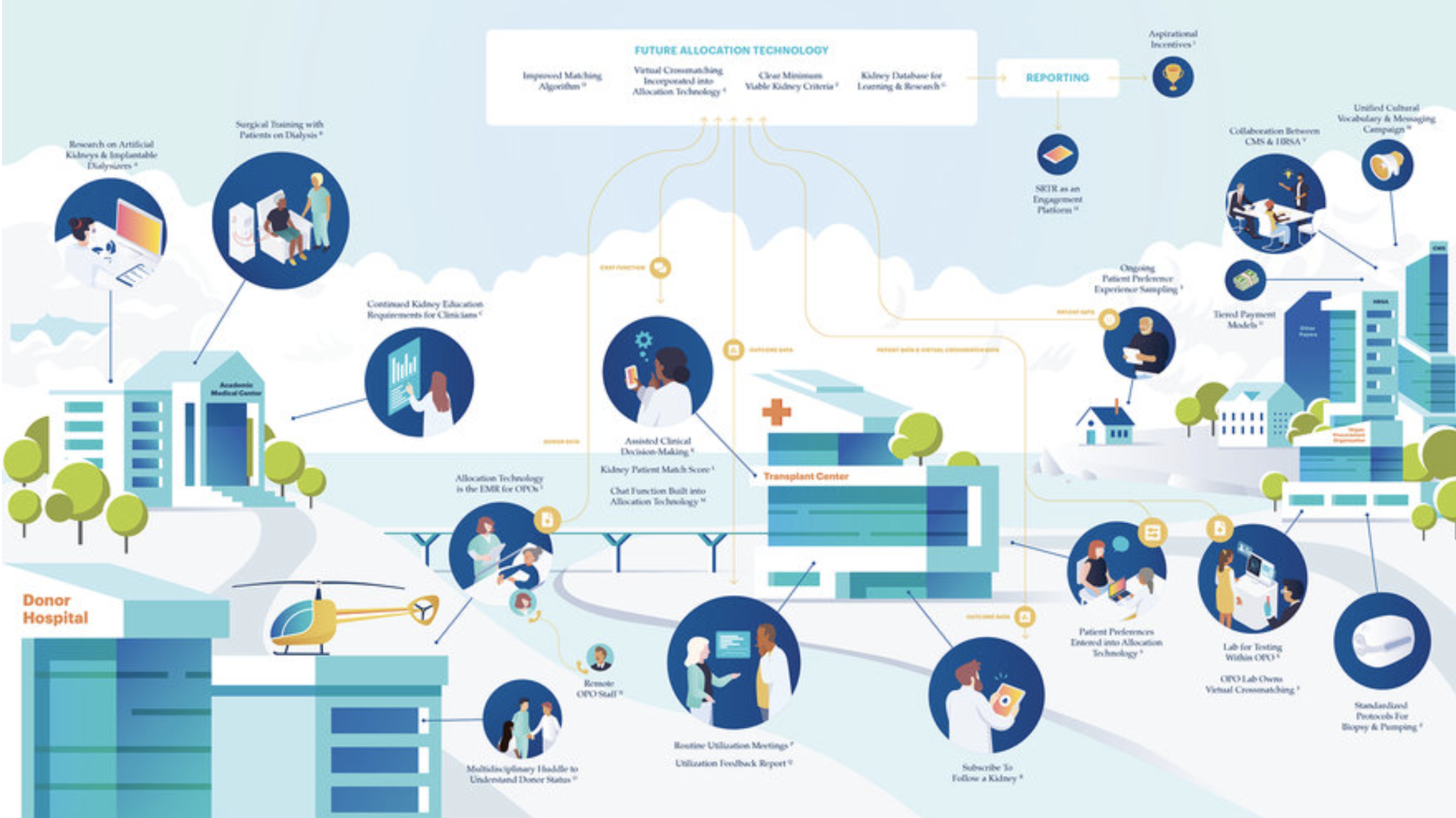

These structural opportunities were the largest method to cascade change into the shared options for all users. Currently, providers must navigate multiple systems for donor and recipient information with manual data entry at almost every step of the organ procurement and allocation process. A single technology source for transplant centers, organ procurement organizations, and donor hospitals to share donor data and organ offers with predictive analytics and real-time feedback could increase speed and decision-making, decreasing cold ischemic time of kidneys.

Another structural opportunity lies within defaults of the applications. For example, the current system requests users to give a "provisional yes" to an organ offer, versus a committed yes or no, which causes additional delays. In transplant center evaluation, we also discovered opportunities to create incentives, rather than just disincentives, which could inspire, rather than restrict, the natural curiosity and patient-centered drive of clinicians. Lastly, US policies could benefit from improved the nuance in matching, such as stratifying "old for old" — matching elderly donors with elderly recipients — existing policy in nations like France. These measures could decrease clinician burden and increase the opportunity to procure an expanded criteria of donors.

We also noticed opportunities for the system to influence individual and local behavior. We applied a behavioral science lens to understand why individuals across this ecosystem make the decisions they make every day.

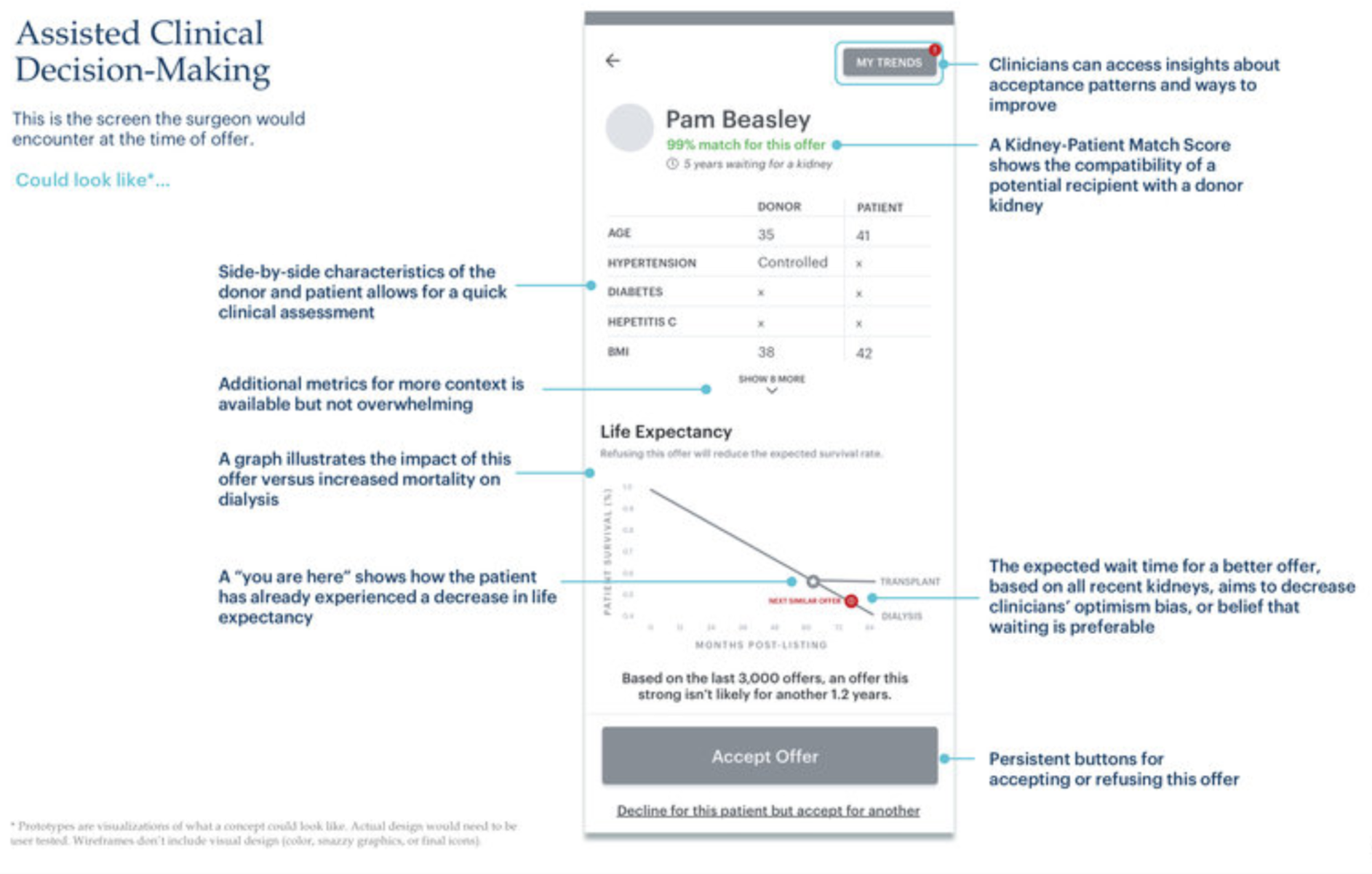

A host of behavioral opportunities abound in the current system. Risk aversion, for example, plays a major role in shaping how organ offer decision-makers (typically transplant surgeons) view kidney offers. Surgeons don't want to transplant a kidney they believe could put their patient or transplant program at risk: these risks seem more temporally powerful than the patient's long-term gains. Cognitive burden among surgeons is also evident; while the organ allocation technology provides clinical information on the organ donor, the surgeon must use their best clinical judgment to compare that data to the clinical characteristics of their patient. Frequently, there is no clear answer; without the aid of assisted clinical decision-making, it is a multivariate decision that usually comes down to intuition.

Labeling bias is also present in decision-making. Each kidney that enters the allocation system is assigned a quality score called the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI). Kidneys with scores above 85, likely from an older, less healthy donor, are more likely to be rejected and ultimately discarded if surgeons and patients decline them. However, research has shown that even kidneys with high KDPI are, in most cases, better for a patient's health than staying on dialysis. The predictive value of KDPI is marginally better than a coin toss. Yet the KDPI label can sway surgeons and patients to reject a kidney. Other, smaller details in the kidney offer — like a patient's number on the match list — also inflict labeling bias in clinicians. Information cascade takes effect when it's obvious that many other surgeons have already declined that kidney.

Availability bias also takes effect. Surgeons make their best determination based on the information most readily available to them. One nephrologist told us: "Transplant surgeons' decisions will depend on their last five surgeries." In other words, if their last few transplants, even of marginal kidneys or high-risk patients, were successful, they were more likely to have wider acceptance criteria when evaluating subsequent kidney offers. This is availability bias at work: the tendency to rely on immediately available examples that come to mind when evaluating a decision. We found this created either a virtuous or vicious cycle of patient and kidney selection.